Dr. Rhonda Franklin became an electrical engineer by accident—or as she says, “through the process of elimination.” When she was a senior in high school, her physics teacher encouraged her to attend a National Science Foundation summer camp, now called PROMES. The forum immediately sparked her interest in STEM studies. Yet it was a presentation on engineering that caught her attention—and ultimately set her on the path to her chosen career.

“It came down to mechanical engineering or electrical engineering. I liked the mechanical aspect, but I didn’t like getting my hands dirty, so I chose electrical engineering,” she recalls. “Electrical engineering uses the most math, requires practical analysis, and plays a role in many types of communications, all aspects that appealed to me. It became the career path I wanted to pursue.”

Blazing a path in electrical engineering, which also had few minorities, didn’t dissuade Franklin from following her dreams. The support she continually received from her parents and teachers helped prepare her for the academic road ahead.

“When I shared an idea with them, they always encouraged me to go for it,” Franklin recalls. “And because they told me to try it, I always did. Even if they knew nothing about the subject, such as electrical engineering, they urged me to explore the field and pursue my goals.”

Achieving Academic Excellence and Making History

That support gave Franklin the confidence to achieve her academic aspirations—and more. In 1988 she obtained her bachelor's degree in electronic engineering at Texas A&M University. She went on to earn a master’s, and eventually a doctorate, from University of Michigan in 1995, where she also made history, becoming the first African American woman in the university’s microwave engineering program. Franklin was also one of only six African Americans to graduate with an engineering PhD in the United States at the time. Her exposure to graduate research developed from three separate internships as a GEM Fellowship recipient at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Franklin’s work also caught the attention of US government officials who awarded her the National Science Foundation Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) in 1998. PECASE recognizes scientists and engineers who show exceptional potential for leadership in the scientific frontier as they begin their careers. The award is one of the highest honors given to researchers by the US government.

“That was a dream come true,” Franklin says. “It was an awesome moment in my life. I received the award at the White House, and my parents were there to share the amazing experience.”

The honor also included an increase in grant funding worth $500,000, which helped Franklin get her faculty career as a microwave engineer off the ground.

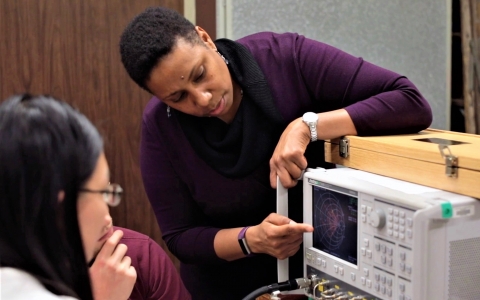

Dr. Rhonda Franklin holding a patch antenna inside an anechoic

chamber, a room designed to completely absorb sounds of reflections

and electromagnetic waves.

Courtesy: UMN College of Science and Engineering

Blazing a Trail on the Frontiers of Innovation

Currently a Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at University of Minnesota, Franklin spends time in the lab creating circuits that operate at high frequencies and can improve communication. “We’re at a point now where we can start developing technology to work faster, moving from gigahertz to terahertz frequencies,” Franklin explains. “This will allow us to create components and products for communication that don’t exist today.”

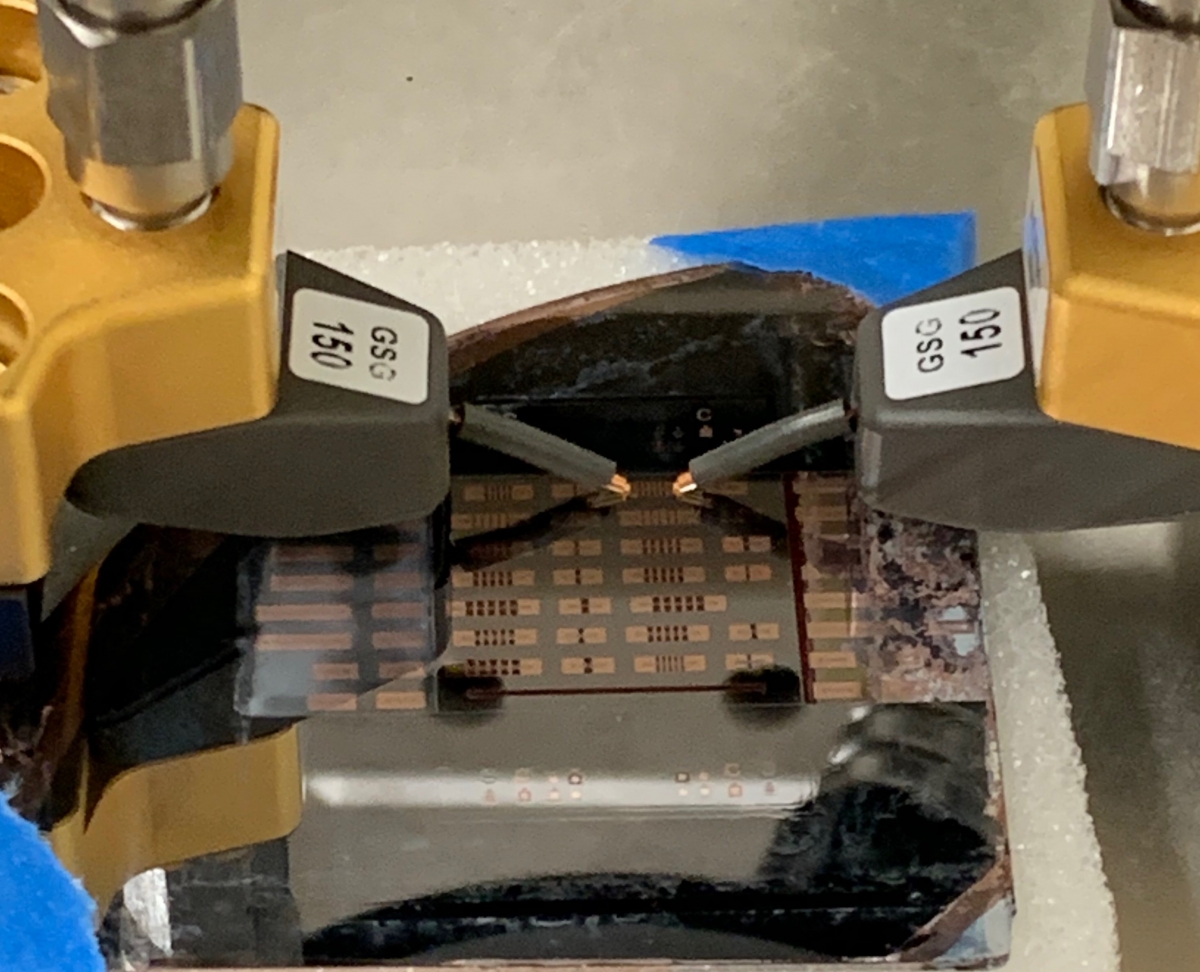

Sample of an integrated circuit with nanowires. Radio frequency

probes are touching the ends of the circuit to make a connection.

Nanowires in the circuits are used to make the connections

between top and bottom transmission lines.

Courtesy: Yali Zhang

Her research and innovations affect communications and nanomedicine applications. In communications, her collaborations with her UMN nanotechnology colleague, Beth Stadler, is advancing 3D packaging and integration to allow more circuit connections within very fast systems.

She is also using nanotechnology to create nanolabels for disease detection in nanomedicine. A recent new area in the NSF Engineering Research Center ATP-Bio, at UMN, she is working on technologies that will help preserve organs.

“Some of the methods we use to understand electronic materials can help us recognize materials medical professionals use in a biological system to preserve organs.” This research, she adds, will enable doctors to keep the organs viable as they are prepared for transplantation into a person’s body.

Sparking Students’ Interest in STEM

Just as important as her scientific explorations and innovations is her outreach work. Influenced by the encouragement she received from her parents, teachers, and professors, Franklin co-created the Inspire program in the Institute of Engineering in Medicine at University of Minnesota. The initiative helps students from diverse communities, in eighth grade through junior and community college level, learn more about careers in the biomedical and healthcare fields.

Her outreach work didn’t end there, however. To garner more interest in engineering, Franklin co-founded the Project Connect program, which exposes women and under-represented minorities to microwave engineering careers by providing information on all aspects of the field, along with professional development skills.

“Faculty and professors play an important role in a student’s destiny. It’s heartwarming to see which field students identify with and hear about their experiences. To me, that’s worth millions.”

University of Minnesota

College of Science and Engineering Spotlight:

Dr. Rhonda Franklin

Inspirational Initiatives Recognized

Franklin’s heartfelt implementation of the university’s mentoring programs did not go unnoticed.

In 2020 Franklin received one of the inaugural Institute of Engineering in Medicine Abbott Professorships in Innovative Education for her work as co-director of the Inspire program. She was honored with the N. Walter Cox Award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers for her “spirit of selfless dedication” to Project Connect. ARCS Minnesota Chapter members also commended Franklin for developing the initiative and named her as the chapter’s 2020 Scientist of the Year.

“It was an honor to receive this recognition from ARCS Minnesota Chapter,” Franklin comments. “ARCS members are passionate about investing in a student’s educational future, as am I.”